United States Paper Money Collection

United States Paper Money Collection United States Paper Money Collection

United States Paper Money Collection

Dorothy Andrews Elston was appointed Treasurer of the United States by President Richard M. Nixon on 08 May 1969. She married Walter Kabis in 1970 and changed her name to Dorothy Andrews Elston Kabis. She became the first (and so far) only treasurer to have their name changed while in office, an event significant given that the signature of both the Treasurer of the United States and the Secretary of the Treasury appear on paper denominations of U.S. currency.

The resulting change in Kabis' signature appeared first on the Series 1969A $1 Federal Reserve Note, along with the signature of Secretary David M. Kennedy. All other denominations had Kabis' new signature along with Secretary John Connally's signature on Series 1969B.

Signatures of Dorothy Andrews Elston Kabis

John B. Connally served as Governor of Texas, and Secretary of the Navy and Treasury under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Richard M. Nixon, respectively. While he was Governor in 1963, Connally was a passenger in the car in which President Kennedy was assassinated, and he was seriously wounded in the shooting, but he survived despite his injuries. John B. Connally served as Governor of Texas, and Secretary of the Navy and Treasury under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Richard M. Nixon, respectively. While he was Governor in 1963, Connally was a passenger in the car in which President Kennedy was assassinated, and he was seriously wounded in the shooting, but he survived despite his injuries.

|

Dorothy Andrews Elston Kabis died of a heart attack in Sheffield, Massachusetts on 03 July 1971 at the age of 54. Romana A. Bañuelos was subsequently appointed Treasurer of the United States.

It is with special pleasure that I have today nominated Romana A. Bañuelos to be Treasurer of the United States.

Since the tragic and untimely death of Dorothy Andrews Kabis on July 3, we have searched the country for a person of truly outstanding credentials and ability to succeed her as Treasurer. I was delighted to find such a person in Mrs. Bañuelos. In her extraordinarily successful career as a self-made businesswoman, Mrs. Bañuelos has displayed exceptional initiative, perseverance, and skill. In addition, as chairman of the board of directors of Pan American National Bank of East Los Angeles, which serves the Mexican-American community of that area, she has not only proven herself a highly able bank executive but has also contributed substantially to the development of that community.

The post of Treasurer of the United States is one of high honor and high responsibility. Mrs. Bañuelos will bring to it a high measure of distinction.

294 - Statement Announcing Nomination of Romana A. Bañuelos as Treasurer of the United States

Richard M. Nixon

September 20, 1971

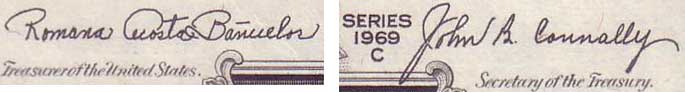

Signature of Romana Acosta Bañuelos

The story of Romana Acosta Bañuelos is a real-life American rags-to-riches adventure. Born into a poor family of Mexican-Americans, she became the first Latina treasurer of the United States (1971-1974) and owner of a multimillion-dollar business, Romana's Mexican Food Products, Inc.

The story of Romana Acosta Bañuelos is a real-life American rags-to-riches adventure. Born into a poor family of Mexican-Americans, she became the first Latina treasurer of the United States (1971-1974) and owner of a multimillion-dollar business, Romana's Mexican Food Products, Inc.

Acosta, daughter of poor Mexican immigrants, was born in the tiny mining town of Miami, Arizona, on March 20, 1925. In 1933, during the Great Depression, the U.S. government deported her family, and thousands of other Mexican-Americans, even though many of the deportees, like Acosta family, had been born in the United States. The Acostases believed the deportation officials' statement that they could return as soon as the country's economy had improved, so they accepted the government's offer to pay for their moving expenses and left their home peacefully.

They moved in with relatives who owned a small ranch in the Mexican state of Sonora. Along with her parents, Acosta began rising early to tend the crops that her father and other male relatives had planted. She helped her mother in the kitchen as well, making empanadas that her mother sold to bakeries and restaurants to make extra money. Acosta later recalled that her mother, who also raised chickens for their eggs, "was the type of woman who taught us how to live in any place and work with what we have." She called her mother a resourceful businesswoman who presented a strong role model for what a woman could do economically with very little.

Acosta married in Mexico at age 16, not an unusually young age in that culture at the time. She had two sons, Carlos and Martin, by age 18, but her husband deserted the family in 1943. She returned to the United States with her children. Some reports speculate she worked in an El Paso, Texas, laundromat for a time, while others say she followed an aunt to Los Angeles. Most accounts describe Acosta arriving in Los Angeles with her children, unable to speak English and with only seven dollars to her name.

Quickly finding employment as a dishwasher during the day and as a tortilla maker from midnight to 6 a.m., Acosta soon began making enough money to save a little. At 21, she married a man named Alejandro and saved about $500, which she used to start her own tortilla factory in downtown Los Angeles. Acosta bought a tortilla machine, a fan, and a corn grinder, and with her aunt helping her she made $36 on the factory's first day of business in 1949.

Ambitious, young, and driven, Acosta looked constantly for opportunities to sell her tortillas to local businesses. As sales volumes increased, she incorporated the company and named it Ramona's Mexican Food Products, Inc. There is some discrepancy as to how the business' name came about: some say the sign painters made a mistake when spelling "Romana"; others insist "Ramona" was an early California folk hero; and still others believe it was a product of people's unfamiliarity with the name "Romana." Regardless, by the mid-1960s, Ramona's Mexican Food Products, Inc. was thriving and Acosta had a daughter, whom she named Ramona after the business.

Romana's Mexican Food Products Logo

In 1963, she was looking for ways to help the struggling Latinos in her neighborhood, Acosta and some businessmen founded the Pan-American National Bank in East Los Angeles. The men had initially approached Alejandro with the proposal, but he was busy with political work and suggested the men talk to Acosta. The bank's main purpose was to bankroll Latinos who wanted to start their own businesses. Acosta also believed that if Hispanics could increase their financial base they would have more political influence and be able to improve their standard of living.

In 1969 Acosta was appointed chairperson of the bank's board of directors and received the city's Outstanding Business Woman of the Year Award. Later that year, Mayor Sam Yorty presented her with a commendation from the County Board of Supervisors, and Acosta established a college scholarship fund, the Ramona Mexican Food Products Scholarship, for poor Mexican-American students.

With bank assets already in the millions and deposits climbing rapidly, Pan-American National's huge success caught the attention of the Richard Nixon's administration. The president was seeking to repay the Hispanic Republic Assembly, which had played a strong role in his election. Acosta agreed to throw her name into the hat when asked in 1970 if she would consider the post of U.S. treasurer. Not believing she had a chance to be nominated and confirmed, Acosta went about her daily life. She was stunned when Nixon personally chose her as his candidate.

During the nomination process, Acosta was even more taken aback by a sudden raid on her tortilla factory by U.S. Immigration Service agents. The agents, contrary to their usual methods, reportedly carried out a loud, disruptive raid through the facility, attracting a lot of press attention and apparently hurting Acosta's chances of securing the treasurer nomination. However, Nixon sided with her and called the raid politically motivated, charging the Democratic Party with instigating it. She was later vindicated when a Senate investigation ruled that the raid was carried out solely to cause embarrassment to the Nixon administration.

Despite the ugly affair, Acosta sailed through the confirmation process to become the nation's 34th treasurer and the first Latina in the position in U.S. history. She took office on December 17, 1971, becoming the highest-ranking Mexican-American in the government. Her daughter would say of Acosta's performance as treasurer, "My mother's legacy is that she ran the place as a business, not just as another wing of the government."

Acosta Bañuelos served as treasurer for one term, until 1974, when she resigned to spend more time with her businesses, family, and philanthropic pursuits. She said during a 1979 interview with Nuestro magazine, "It was a beautiful experience. I will always be grateful to President Nixon." Later that year, Acosta was a founding member of Executive Women in Government.

By 1979, Ramona's was making and distributing 22 different food products. It had more than 400 employees and sales of $12 million a year. The company's success was instrumental in the popularization of Mexican cuisine in the United States. As the Hispanic population of the country grew, of course, so did sales of tortillas, empanadas, and many other traditional favorites. However, other races began to favor the inexpensive, delicious foods as well, boosting the company's profits. Ramona's continued to grow throughout the 1980s, when it became the one of the largest Mexican food distributors and manufacturers in California.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Acosta continued to serve as president of Ramona's and Pan-American National, and by 1992, she had served three terms as chair of the bank's board of directors. However, in the late 1990s, she allowed her three children to take over daily operations of Ramona's and to play large roles in the bank's operations.

Acosta remained CEO at Pan-American National and president of Ramona's, running both businesses from her Los Angeles home. The privately held company distributed nationwide with her daughter was chief financial officer of the bank, which had 30 bilingual employees and three branches. The Acosta family owned two-thirds of the shares in the publicly traded bank. Pan-American National Bank is credited with helping economically troubled East Los Angeles develop a sense of community and with being a vital factor in the economic improvement of its Latino population.

The printing schedules and rapid changes in signatures and Series designation caused a bit of confusion with the Series designation for different note denominations. Series 1969 went into production in in May 1969, using the new 1969 date because the modern English-language Treasury seal was adopted for that Series. Just over a year later, the U.S. Treasurer at the time, Dorothy Andrews Elston, got married while in office, and changed her signature to Dorothy Andrews Kabis, giving us Series 1969A.

Less than six months after that, David Kennedy resigned as Secretary of the Treasury and was replaced by John Connally. This created some weirdness in the series dating, because so far only the $1 had been printed with the Kabis-Kennedy signatures, as 1969A. Therefore, the Kabis-Connally signatures were designated 1969B on the $1, but 1969A on the other denominations. (Collectors are still occasionally confused by this....)

Less than six months after that, Dorothy Kabis died unexpectedly, and after a few months she was replaced as Treasurer by Romana Bañuelos. The resulting Bañuelos-Connally notes were 1969C on the $1, but 1969B on other denominations.

Finally, less than six months after those notes had finally gone to press, Connally stepped down as Secretary and was replaced by George Shultz. That gave us 1969D on the $1 and 1969C on the higher denominations. And the Bañuelos-Shultz signature combination finally lasted for a couple of years, giving the BEP time to catch up.

The next signature combination that came along was Neff-Simon in 1974. It should've been 1969E on the $1, and 1969D on the other denominations. But, possibly desiring to put a stop to the strange split numbering, William Simon told the BEP to designate the new series as 1974 instead. (Of course, not long after, the new $2 FRN was authorised, and it got dated Series 1976, so the Neff-Simon signatures *still* appeared on notes with two different series designations. Sometimes you just can't win, even if you're Secretary of the Treasury!)

Incidentally, of all of the short-lived signature combinations in the 1969 mess, the shortest Bañuelos-Connally.

Also incidentally, there hasn't been another even small design change to the $1 FRN since that new Treasury seal in 1969. Therefore, if William Simon hadn't come along and changed the series-dating rules, the Cabral-Snow $1 FRNs would be called Series 1969R!

| Series | $1 | $5 | $10 | $20 | $50 | $100 |

| 1969 | Elston - Kennedy | Elston - Kennedy | Elston - Kennedy | Elston - Kennedy | Elston - Kennedy | Elston - Kennedy |

| 1969 A | Kabis - Kennedy | Kabis - Connally | Kabis - Connally | Kabis - Connally | Kabis - Connally | Kabis - Connally |

| 1969 B | Kabis - Connally | Bañuelos - Connally | Bañuelos - Connally | Bañuelos - Connally | ||

| 1969 C | Bañuelos - Connally | Bañuelos - Schultz | Bañuelos - Schultz | Bañuelos - Schultz | Bañuelos - Schultz | Bañuelos - Schultz |

| 1969 D | Bañuelos - Schultz |