An interesting article on the conflicts between fuel economy and noise, and the technologies involved.

CFMI Trying To Anticipate New Climate Challenges (Subscription Required)

Aviation Week & Space Technology

06/04/2007, page 52

Michael Mecham

Evendale, Ohio

. . . and some new ones, as CFMI tackles fuel costs and environmental concerns

Printed headline: Some Old Plans . . .

It came as no surprise to CFM International that prospective customers of next-generation single-aisle aircraft rank reduced fuel consumption as their highest priority. But they also are awakening to a broadening of the clean planet debate that is likely to lead to a series of new regulations, such as carbon trading, from governments eager to respond to the growing clamor to do something about global warming.

Recently, CFMI, the 50-50 partnership between General Electric and Snecma, surveyed lessors, banks, legacy and low-cost carriers (LCCs) about their priorities for the LEAP56 (Leading Edge Aviation Propulsion) initiative for 18,000-33,000-lb.-thrust-class engines the company launched in 2005 to power a successor to the Airbus A320 and Boeing 737 families.

……

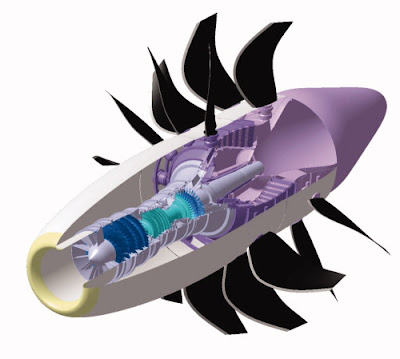

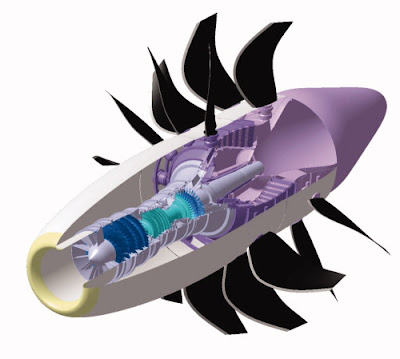

CFMI likes what open rotors, whether in pusher (right) or puller configurations, can do to lower fuel burn. But noise and installation issues will make them a challenge. Credit: CFM CONCEPTS

But another bit of feedback is a sign of the times. “Focus on CO2,” the LCCs advised. European political leaders have been the most pronounced adherents of the global warming message, which is to decrease levels of carbon dioxide from man-made sources. But the idea that increased regulation is necessary is gaining acceptance elsewhere.

“In the last six months, we have been impressed by how much the debate has picked up in the U.S.,” says CFMI President and CEO Eric Bachelet.

…..

We can thank Al Gore for this.

Since CO2 emissions are directly related to fuel burn, reducing specific fuel consumption (SFC) is the most effective way to address the issue. The LEAP initiative is based on dropping SFC 10-15%, maintenance costs by about 15% and noise by 10-15 dB. to meet requirements expected in the next round of noise regulations, Stage 4, says Planaud. Additionally, oxides of nitrogen (NOx) emissions will need to exceed by 60% the Committee of Aviation Environmental Protection (CAEP) 6 standards that come into effect next year.

Rig tests of the compressor, combustor and high- and low-pressure turbines in the initiative will begin this year at Snecma’s facilities in Villaroche, France, and GE’s at Peebles, Ohio. The tests are aimed at an engine launch in 2011, which is enough lead time for Airbus and Boeing to introduce a successor to their A320 and 737 programs, respectively, by mid-decade.

….

Started in 2005, LEAP56 includes composite fan case and fan blades, titanium aluminide 3D airfoils in the low-pressure turbine, ceramic matrix composite high-pressure turbine nozzles and a second-generation twin-annular pre-mixing swirler (TAPS) combustor. Clapper calls the combined technologies a “step change” for CFMI.

Composite fan blades are one of the most intense technology development efforts. GE introduced them on the GE90 and has extended the concept with composite fan cases for the GEnx. Those composites are laid in plies pre-impregnated with resin, a laborious process that GE tried without much success to automate. Besides saving weight and cutting SFC, composite blades are slashing maintenance costs. Only three blades have had to be replaced on GE90s since the engine entered service in 1995. Composite blades are so durable that GE is aiming for their certification on the GEnx with no service life limits (AW&ST Apr. 16, p. 60).

Using 18 wide-chord composite blades, rather than the customary 22 or more on older designs, combined with a composite fan case will save 400 lb. on LEAP engines, says Planaud.

However, the company anticipates LEAP56 production rates comparable to CFM56 engines, which have been as high as 2,000 a year, about five times higher than the GE90/GEnx series. As a result, the CFMI partners have been looking for composite manufacturing techniques that can be automated. Most promising is a process called Resin Transfer Molding (RTM) in which bands of dry preform are woven rather than laid on top of each other to create the composite structure.

The strength of small composite blades is an issue. The big GE90 wide-chord fan blades–as much as 115 in. long–have proven adept at dissipating the shock of bird and other foreign object strikes. But the smaller LEAP56 blades have less surface area to absorb such shocks. Tests on a CFM56-5C using 70-in. RTM blades will be done this year.

While noise, NOx, carbon particulate and carbon dioxide emissions are a growing political issue, the size of their fuel bill remains the biggest sore point for airlines.

All the world’s airlines combined spent $43 billion on fuel in 2001–13% of their direct operating costs (DOC)–when Jet A cost $0.66 per gallon. At current rates of $2.03 per gallon, the bill for all airlines combined will hit $117 billion this year, or 26% of DOC, says Clapper.

To tackle this problem, CFMI assigned a team to use a combination of computer studies and the company’s experience in maintenance to consider alternative engine designs. Most were rejected.

Among them were the geared turbofan (GTF) that Pratt & Whitney is developing. Its large-diameter, slower fan is expected to benefit fuel burn, but also will increase weight and drag, the CFMI team concluded. And the GTF was seen as driving up maintenance costs. Similarly, a two-stage turbine will be more efficient, but its higher operating temperatures are a worry sign for maintenance.

So the company ended up with a single-stage turbine, but with a higher pressure ratio for improved combustor efficiency than current models. “It’s a simple, rugged design with fewer parts and higher reliability,” says Clapper.

Looking beyond LEAP56, Snecma has been pursing an alternative strategy that holds some promise: a counterrotating fan to boost bypass.

More radically, CFMI has dusted off the unducted fan concept first proposed in the late 1980s as a weight-savings approach to lowering fuel costs in response to the industry’s first oil shock. That idea faded in the early 1990s when fuel prices receded. But with fuel high again, and likely to stay that way because worldwide energy demands have increased so much, CFMI is taking a second look at unducted fans, which it’s renamed “open rotors.”

Last October, Rolls-Royce noted that it is exploring unducted fans, too. Pratt says mounting and noise issues are too great a hurdle and is sticking with its geared turbofan (AW&ST May 28, p. 65).

Without the weight and drag of an engine nacelle, CFMI calculates that a counter-rotating open rotor will save 10% in SFC beyond the improvements it foresees from LEAP56. Fans in both tractor (puller) and pusher configurations are under study. Using twin rows of blades improves their efficiency and allows slower speeds to reduce noise, Klapproth says.

An ultra-high bypass ratio, on the order of 35:1, is possible–four times the 9:1 ratio expected from LEAP56 and seven times the current CFM56 ratio of 5:1. Pressure ratios would be about 15:1, similar to LEAP56, but well ahead of the CFM56’s 11:1.

But the open rotors are noisy, about 10% noisier than the LEAP engine, meaning cabins will need additional insulation. At its best, the engine is unlikely to meet the 20-dB. effective perceived noise reduction that the company foresees by 2020, Clapper acknowledges.

The largest CFM56 produced now, the -5C for the A340-300, has a 72-in. fan diameter. An equivalent-sized engine with an open rotor will require a 12-14-ft.-dia. rotor, posing significant challenges for mounting and certification.

Regardless of how well open rotor technology works, it’s unlikely to appear until late in the next decade “at the earliest,” says Clapper.

The noise issue alone could doom it. While engine makers are confident they can continue to lower fuel burn, which directly reduces CO2 emissions, and reduce NOx/carbon particulate pollution, they are increasingly worried about their ability to do so while simultaneously reducing noise because the technologies to do the former work against the latter.

Noise tends to be a local issue, emissions more national and international. So there’s the possibility of an interesting debate taking place. It may be decided pragmatically. The pain of higher fuel bills may be so great that it will drive compromises that will still benefit the environmental camp, but work against those fighting to reduce engine noise.

My guess is that this will be changed with new forms of zoning that get residences away from airports. In a battle between global warming, and local noise, the localities lose.

Boeing would modify an external fuel tank to fit the F/A-18E/F with a centerline-mounted IRST. Lockheed Martin would provide the critical optics.Credit: BOEING CONCEPTS>

Boeing would modify an external fuel tank to fit the F/A-18E/F with a centerline-mounted IRST. Lockheed Martin would provide the critical optics.Credit: BOEING CONCEPTS>